- Home

- Mark Hodder

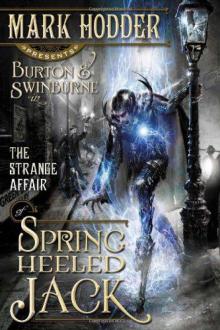

The strange affair of Spring-heeled Jack bas-1 Page 7

The strange affair of Spring-heeled Jack bas-1 Read online

Page 7

He now spoke to her in her own dialect: "You have fallen under a spell, young lady. I recognise the signs, as you, a nurse, would recognise the symptoms of an illness. The presence of a newly opened bottle of laudanum on your dresser suggests to me that you are suffering from a headache. This further leads me to believe that you've experienced a traumatic shock and the memory of it has been sealed within the depths of your mind. Believe me when I say that it will do you no good if it remains there, hidden away like a festering cancer. It must be sought out, exposed, and acknowledged; confronted, subdued, and defeated. Sister Raghavendra, I possess the power of magnetic influence. If you permit it-if you place yourself under my protection and send this worthy old woman away-I may be able to break through the spell to discover that which is concealed. My intentions concern only your well-being; you should fear neither me nor my skill as a mesmerist."

The nurse looked up and her exquisite eyes were wide with wonder and delight.

"You speak my tongue!" she exclaimed, in her own language.

"Yes, and I know Bangalore. Will you trust me, Sister?"

She reached out her hands to him; he leaned forward and took them.

"My name is Sadhvi," she breathed. "Please help me to remember. I don't want to lose my job without even knowing the reason why."

"Here," interrupted Mrs. Wheeltapper, wheezily. "What's all this? I'll brook no hanky-panky in my premises! And what was all that gobbledygook? Not sweet nothings, I hope; not bold as brass in front of a poor old widow woman!"

Burton smiled at her and released the nurse's hands.

"No, Mrs. Wheeltapper, nothing like that. It just so happens that I know the sister's town of birth and speak her native language. She was moved to hear it again."

"It's true," put in the nurse. "You cannot imagine, Mrs. Wheeltapper, how it gladdens my heart to be so reminded of my childhood home!"

The old lady threw up her hands.

"Ooooh!" she cried, with more life in her voice than Burton had heard yet. "Ooooh! How lovely! How wonderful for you, my dear!"

"It is! It is!" Sister Raghavendra nodded. "Ma'am, I feel positive that you can trust the good captain to behave with the utmost decorum. I would speak with him awhile, if you don't mind, in my own tongue; of his travels in my homeland. It would be dreadfully boring for you. Why not continue with whatever you were doing? I smell cooking-were you performing miracles in the kitchen again?"

The landlady raised a gnarled hand to her veil and tittered behind it.

"Silly girl!" she chortled. "You know very well that Polly cooks to my directions and inevitably adds her own special ingredient: utter incompetence!"

The three of them laughed.

"Mrs. Wheeltapper," said Burton, "a few months ago the monarch honoured me with a knighthood. I can give you my word that I would never tarnish that title with any act of impropriety."

Even as he spoke, Burton wondered whether he could trust himself to keep such a promise.

"Good gracious!" the old widow cooed. "A knight! A `sir' in my own home! Well I never did! I never did indeed!"

She reached up and lifted her veil. The baggy, liver-spotted face beneath, as ancient as it was, had obviously been attractive in its day, and was made so again by the unrestrained smile that it directed at the famous explorer. Two teeth were missing, the rest were yellowed, but the pale blue eyes twinkled with good humour, and Burton couldn't help but grin back.

"Forgive me!" pleaded the widow. "I treated you like a common visitor when you are obviously a man of culture, as was my dear Tony, may he rest in peace. I shall give you both your privacy!"

She stood.

Burton got to his feet and escorted her to the door.

"A gallant gentleman!" she sighed. "How lovely!"

"It has been a delight to meet you, Mrs. Wheeltapper. I shall talk with Sister Raghavendra awhile, then depart-but may I call again some time? I know of the 17th Lancers and would be very much interested in hearing of your late husband's service with them."

A tear trickled down the old woman's cheek. "Captain Sir Burton, sir," she said, "you are welcome to call on me whenever the inclination takes you!"

"Thank you, ma'am."

He closed the door after her and returned to Sadhvi Raghavendra, who, in truth, was the real reason he might consider a repeat visit to 3 Bayham Street.

"What do you know of mesmerism?" he asked as he sat down.

"I saw it practised many times when I was a child," she replied.

"Are you scared of it?"

"No. I want to know what it is that I can't remember. If that means placing me in a trance, so be it."

"Good girl. Wait a moment-let me pull this chair a little closer."

Burton shifted the armchair until he was sitting face to face with the nurse. He looked her in the eye and spoke in her language.

"Allow yourself to relax. Keep your eyes on mine."

Two pairs of dark, fathomless eyes locked together.

"You have long lashes," said the girl.

"As do you. Don't speak now. Relax. Copy my breathing. Imagine your first breath goes into your right lung. Inhale slowly; exhale slowly. The next breath goes to the left lung. Slowly in. Slowly out. And the next into the middle of your chest. In. Out."

As her respiration adopted the Sufi rhythm he was teaching her, Sister Raghavendra became entirely motionless but for an almost undetectable rocking, which Burton could see was timed to her heartbeat.

He murmured further instructions, guiding her into a cycle of four breaths, each directed to a different part of her body.

Her mind, subdued by the complexity of the exercise, gradually gave itself over to him. He could see it in her luminous eyes, as her pupils expanded wider and wider.

Suddenly, the black circles closed inward from the sides, forming perpendicular lines, and the deep brown irises blazed a bright pink. Something malevolent regarded him.

Burton blinked in surprise but the illusion-if that's what it was-was gone in an instant.

Her eyes were brown. Her pupils were wide black circles. She was entranced.

Recovering himself, he spoke to her: "I want you to return to last night; place yourself in Penfold Private Sanatorium, in Lieutenant Speke's room. You've been reading to him but now you are interrupted. A man enters the room."

"Yes," she replied softly. "I hear a slight creak as the door swings open. I look up from my book. There is a footstep and he is there."

"Describe him. In detail."

A shudder ran through her body.

"Such a man! I've never seen the like! His frock coat is of crushed black velvet; his shirt, trousers, shoes, and hat are all black, too; and his pointed fingernails are painted black; but his skin and hair-straight hair, so long that it falls past his collar-they are whiter than snow! He's an albino! There is no trace of colour on him except in the eyes, which are of a dreadful pink with vertical pupils like a cat's."

Burton started. Those same eyes had looked out of the girl's head just moments ago!

"There is something wrong with his face," she continued. "His upper and lower jaws are pushed a little too far forward, almost forming a muzzle, and his teeth-when he smiles-are all canines! He enters the room, looks at the lieutenant, looks at me, then tells me to fetch a trolley. I must obey. It's as if I have no will of my own."

"So you leave the room?"

"For a moment, and when I return there are three-three-"

She stopped and whimpered.

"Don't worry," soothed Burton, "I am here with you. You are perfectly safe. Tell me what you can see in the room."

"There are three men. I-I think they are men. Maybe something else. They are short and wear red cloaks with hoods and they are each sort of-sort of twisted; their bodies are too long and too narrow in the hip; their chests too deep and wide; their legs too short. Their faces, though-their faces are-"

"Yes?"

"Oh, save me! They are the faces of dogs!"

; Burton sat back in surprise. He reached into his jacket and drew the sketch by Dore from his pocket. He unfolded it and showed it to the girl.

"Like this?"

She recoiled away from him and began to tremble violently.

"Yes! Please-please tell me-what are they?" Her voice rose in volume and pitch. "What are they?"

He took her hands in his and stroked their backs with his thumbs. Her skin felt smooth, soft, and warm. The heady scent of jasmine filled his nostrils.

"Shhh. Don't be afraid. It's over, Sadhvi. It is in the past."

"But they aren't human!"

"Perhaps not. Tell me what happens next."

"I walk back into Lieutenant Speke's room with the trolley, see the-the three things-then the albino jumps from behind me and restrains me, with a hand over my mouth. He is so strong! I can't move! The dog-log-menthey lift Lieutenant Speke from his bed, place him on the trolley, and wheel him out of the room."

"There are no other nurses? No one else sees them?"

"No, I don't think so-but you have made me realise something: the sanatorium, or at least this wing of it, seems very quiet; more so than it should be, even at such an early hour."

"So the dog creatures leave the room-and then?"

"Then the man turns me, looks into my eyes, and tells me to forget; to remember only that Speke's family took the lieutenant. He leaves the room and I follow him along the corridor toward reception. I feel strange. There are nurses standing motionless and, as he passes them, he says something to each in a low voice. We reach reception, and I see the trolley standing empty by the desk. The albino orders me to move over to it and I obey. He speaks to the nurse at the desk and she starts to blink and look around. Then he walks toward the main door and, as he passes me, he says, `Awake!"'

She sighed and visibly relaxed. "He's gone."

"And now you find yourself pushing the trolley and remembering nothing of what just happened?" put in Burton.

"Yes."

"Very well. Close your eyes now. Concentrate on the rhythm of your breathing."

Sister Raghavendra's hands fell from his and she leaned back on the sofa. Her head drooped.

"Sadhvi," he murmured, "I'm going to count down from ten. With each number, you will feel yourself awakening. When I reach zero, you will be fully conscious, alert, refreshed, and you will remember everything. You will not be afraid. Ten. Nine. Eight. Seven-"

As he counted, her eyelids fluttered and opened, her pupils shrank into focus, she looked at him, her hand flew to her mouth, and she cried: "Dear God! Did that really happen?"

"Yes, Sadhvi, it happened. A combination of shock and mesmeric suggestion caused you to bury the memories-but we have managed to uncover them."

"Those dog-things were abominations!"

"I suspect the Eugenicists have been at work."

"They can't! They can't do that to humans!"

"Maybe they didn't, Sadhvi. Maybe they did it to dogs. Or to wolves."

Her eyes widened. "Yes," she whispered. "Wolves!"

"What's the motive for abducting Speke, though? That's what puzzles me," continued Burton, thoughtfully. He stood up. "Anyway-thank you, Sister Raghavendra. You've been very helpful."

She rose from the sofa, stepped forward, and placed her hands on his chest.

"Captain, that albino fellow-he's-he's evil. I felt it. You will be careful, won't you?"

Burton couldn't help himself; his hands slipped around her slim waist and he pulled her close, looking down into her deep, soulful eyes.

"Oh!" she gasped-but it wasn't a protest.

"I'll be careful," he whispered throatily. "And when the mystery is solved, shall I return to tell you about it?"

"Yes. Come back, please, Captain Burton."

It was midday, but London, buried in the heart of the congealing fog, was deprived of light. It tried to generate its own-gas lamps and windows blazed into the murk, but their fierce illumination was immediately crushed and reduced to vague patches of yellow, orange, and red. Between them, the vast and sickening gloom writhed like a living entity, consuming all.

"That you, guv'nor?" came a gruff voice from above.

"Yes, Mr. Penniforth. You're still breathing?"

"Aye. Been 'avin' a smoke o' me pipe. There ain't nuffink like a whiff o' Latakia for fumigatin' the bellows! Get yourself comfy while I light the bull's-eyes. An' call me Monty."

Burton climbed into the hansom. "Bellows?" he grunted. "I should think your lungs are more like a couple of turbines if they can deal with that fog and Latakia! Take me to Scotland Yard, would you?"

"Right ho. Half a mo', sir!"

While his passenger settled, Penniforth climbed down from the box, struck a lucifer, and put the match to the lamps hanging from the front of the engine, and the front and rear of the cabin. He then hoisted himself back up, wrapped his scarf around the lower half of his face, straightened his goggles, gave the peak of his cap a tug, and took hold of the steering bars.

The machine coughed and spluttered and belched smoke into the already laden atmosphere. It lurched away from the curb, pulling the cab behind it.

"Hoff we go, into the great unknown!" muttered Penniforth.

As he carefully steered the machine out of Mornington Crescent and into Hampstead Road, there came a mighty crash and tinkling of broken glass from somewhere far to the left.

"Watch out!" he exclaimed softly. "You don't want to be drivin' into a shop window, do you! Irresponsible, I calls it, bein' in charge of a vehicle in these 'ere weather conditions!"

By the time the hansom cab reached Tottenham Court Road, the "blacks" were falling: coal dust coalescing with particles of ice in the upper layers of fog before drifting to the ground like black snowflakes. It was an ugly sight.

Penniforth pushed on, guided more by instinct and his incredible knowledge of the city's geography than by his eyes. Even so, he steered down the wrong road on more than one occasion.

The steam-horse gurgled and popped.

"Don't you start complainin'!" the cabbie advised it. "You're the one wiv a nice hot boiler! It's cold enough up here to freeze the whatsits off a thingummybob!"

The engine emitted a whistling sigh.

"Oh, it's like that, is it? Feelin' discontentified, are you?"

It hissed and grumbled.

"Why don't you just watch where you're a-going and stop botherin' me wiv the benny-fits of your wisdom?"

It rattled and clanged over a bump in the road.

"Yup, that's it, of girl! Giddy up! Over the hurdles!"

The hansom panted through Leicester Square and on down Charing Cross Road, passing the antiquarian bookshops-whose volumes were now both obscure and obscured-and continuing on to Trafalgar Square, where Monty had to carefully steer around an overturned fruit wagon and the dead horse that had collapsed in its harness. Apples squished under the hansom's wheels and were ground into the cobbles; the resultant mush was quickly blackening with falling soot.

Along Whitehall the engine chugged, then left into Great Scotland Yard, until, outside the grim old edifice of the police headquarters-a looming shadow in the darkness-Penniforth brought it to a standstill.

"There you go, guv'nor!" he called, knocking on the roof.

Sir Richard Francis Burton disembarked and tossed a couple of coins up to the driver.

"Toddle off for a pie and some ale, Monty. You deserve it. If you get back here in an hour, I'll have another fare for you."

"That's right gen'rous of you, guv'nor. You can rely on me; I'll be 'ere waitin' when you're ready."

"Good man!"

Burton entered Scotland Yard. A valet stepped forward and took his coat, hat, and cane, shaking the soot from them onto the already grimy floor.

Burton crossed to the front desk. A small plaque on it read: J. D. Pepperwick-Clerk. He addressed the man to whom it referred.

"Is Detective Inspector Trounce available? I'd like to speak with him, if possible."

"Your

name, sir?"

"Sir Richard Francis Burton."

The clerk, a gaunt fellow with thick spectacles, a red nose, and a straggly moustache, looked surprised.

"Not the explorer chappie, surely?"

"The very same."

"Good gracious! Do you want to talk to the inspector about yesterday's shooting?"

"Perhaps. Would you take a look at this?"

Burton held out his authorisation. The clerk took it, unfolded it, saw the signature, and read the text above it with meticulous care, dwelling on each separate word.

"I say!" he finally exclaimed. "You're an important fellow!"

"So-?" said Burton slowly, suggestively inclining his head and raising his eyebrows.

The clerk got the message. "So I'll call Detective Inspector Trounce-on the double!"

He saluted smartly and turned to a contrivance affixed to the wall behind him. It was a large, flat brass panel which somewhat resembled a honeycomb, divided as it was into rows of small hexagonal compartments. Into these, snug in circular fittings, there were clipped round, domed lids with looped handles. A name was engraved onto each one.

The clerk reached for the lid marked "D. I. Trounce" and pulled it from the frame. It came away trailing a long segmented tube behind it. He twisted open the lid and blew into the tube. Burton knew that at the other end a little valve was popping out of an identical lid and emitting a whistle. A moment later a tinny voice came from the tube: "Yes? What is it?"

Holding its end to his mouth, the clerk spoke into it. Though his voice was muffled, Burton heard him say: "Sir Richard Burton, the Africa chap, is here to see you, sir. He has, um, special authorisation. Says he wants to talk to you about the shooting of John Speke at Bath yesterday."

He transferred the tube to his ear and listened, then put it back to his mouth and said, "Yes, sir."

He replaced the lid, lifting it back to its compartment, the tube automatically snaking in before it.

He smiled at Burton. "The inspector will see you straightaway. Second floor, office number nineteen. The stairs are through that door there, sir," he advised, pointing to the left.

Burton nodded and made for the doors, pushed through them, and climbed the stairs. They were wooden and needed brushing. He came to the second floor and moved along a panelled corridor, looking at the many closed doors. The sound of a woman weeping came from behind one.

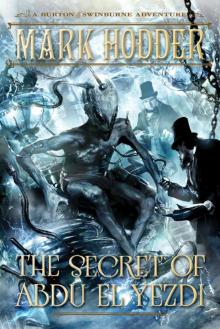

The Secret of Abdu El Yezdi

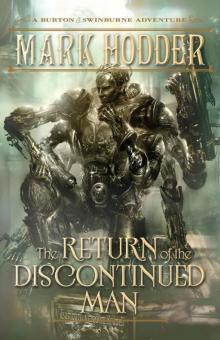

The Secret of Abdu El Yezdi The Return of the Discontinued Man

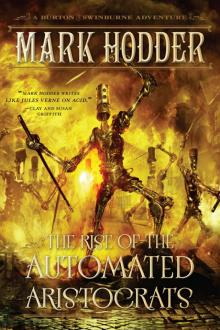

The Return of the Discontinued Man The Rise of the Automated Aristocrats

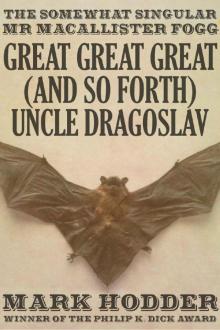

The Rise of the Automated Aristocrats Macallister Fogg 2: Great Great Great (And So Forth) Uncle Dragoslav

Macallister Fogg 2: Great Great Great (And So Forth) Uncle Dragoslav Sexton Blake and the Great War

Sexton Blake and the Great War A Red Sun Also Rises

A Red Sun Also Rises Macallister Fogg 3: The Hetrodythermaline Highwayman

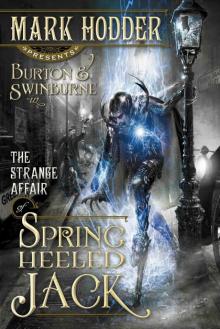

Macallister Fogg 3: The Hetrodythermaline Highwayman The Strange Affair of Spring Heeled Jack

The Strange Affair of Spring Heeled Jack Macallister Fogg 1: The Master Mummer's Mummy (The Adventures of Macallister Fogg)

Macallister Fogg 1: The Master Mummer's Mummy (The Adventures of Macallister Fogg) Expedition to the Mountains of the Moon bas-3

Expedition to the Mountains of the Moon bas-3 The Return of the Discontinued Man (A Burton & Swinburne Adventure)

The Return of the Discontinued Man (A Burton & Swinburne Adventure) Red Sun Also Rises, A

Red Sun Also Rises, A The curious case of the Clockwork Man bas-2

The curious case of the Clockwork Man bas-2 The strange affair of Spring-heeled Jack bas-1

The strange affair of Spring-heeled Jack bas-1