- Home

- Mark Hodder

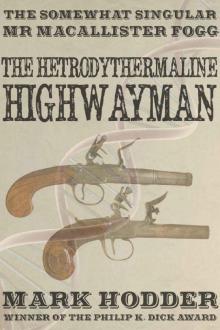

Macallister Fogg 3: The Hetrodythermaline Highwayman

Macallister Fogg 3: The Hetrodythermaline Highwayman Read online

THE ADVENTURES OF THE SOMEWHAT SINGULAR MR MACALLISTER FOG

3

THE HETRODYTHERMALINE HIGHWAYMAN

MARK HODDER

Text copyright © 2013 Mark Hodder

All Rights Reserved

To Ann Lacey

I

Macallister Fogg woke up feeling decidedly peculiar. He sat, with his eyes shut, and assessed the situation.

Must have dropped off in my armchair! Not without precedent. Did the same thing yesterday. And the day before. Come to think of it, it’s a common occurrence.

He shifted his hips and frowned.

Except this doesn’t feel like my chair! It’s bloomin’ hard!

Light was shining through his eyelids. He blinked. It wasn’t the orange glow of gas lamps, and it wasn’t daylight. Rather, it was an incandescent brilliance, unlike anything he’d seen before. He squinted and raised a hand against it.

A slim hand.

A woman’s hand.

“Crikey!” he cried out, and the tone was rich and mellow and undeniably female.

“What the heck?” Again. Female.

He lowered his arm, his eyes adjusted, and he looked down at himself and saw long shapely legs clad in black trousers, slim arms, a flat stomach, and—shock of all shocks—breasts pressing against a plain, indecently tight-fitting, white shirt.

“I—it—what—how—Cor blimey!” he exclaimed.

“Try to stay calm. Everything’s fine,” came a voice, male, from just in front of him.

Fogg looked up and saw that he was in a white rectangular room, completely unfurnished, unadorned, and uninhabited but for him and the young gentleman—sitting in a chair facing him—who’d just spoken.

“How are you feeling?” the man asked.

“I’ve bloomin’ well got a woman’s bloomin’ body! How do you bloomin’ well think I’m bloomin’ well feeling? Where in the name of God am I?”

“That will take a little explaining. But I assure you, you haven’t been harmed and you’re not in any danger. Would you tell me your full name, please?”

“I’m Macallister Edwin Fogg. And who might you bloomin’ well be?”

He winced. It didn’t feel right, hearing all that bad language being spoken by a woman, even if, as appeared to be the case, he was the woman in question.

“I’ll answer that in a moment, but first, what is your birthdate, Mr Fogg?”

“The 28th of November, 1820.”

The man—he was wearing a white laboratory coat—was fairly well built, and appeared to be in his mid-thirties. He lifted a document, ran his eyes over the top page, turned to the second, and said, “Ah. Here you are! Excellent! An unqualified success!” He looked up and smiled. “Mr Fogg, I’m Professor Xavier Macallister Fogg the Second. I’m your five-times-great grandson, this is the year 2084, and you currently inhabit the body of my sister, your five-times-great granddaughter, Doctor Miriam May Fogg.

“Balderdash!”

“Not at all, sir. Tell me, what year do you think it is?”

“1857.”

“Ah, right in the middle of your lifespan. That’s interesting.”

“It isn’t. It’s preposterous. Whatever it is.”

Fogg pushed himself to his feet, looked around, and saw that the wall behind him was one enormous mirror. He was reflected in it; a pretty young woman with long blonde hair and thoroughly improper clothing.

He collapsed back into the chair.

“Try to maintain your composure, Mr Fogg, while I explain,” the professor said. “You won’t have heard of DNA—Deoxyribonucleic acid—though it was discovered in your lifetime. 1869, in fact. We call it the ‘building block of life.’ It is a very highly complex component of your body, which carries coded instructions that dictate your physiological characteristics. To put it in the most basic terms possible, when you procreate—”

“I say! Steady on!” Fogg objected.

“Forgive me, sir; I make the reference strictly in the context of science.”

Fogg cleared his throat and habitually reached to take a cigar from his jacket’s top pocket. His fingers encountered a breast. He cleared his throat again, more loudly, and quickly dropped his hand to his lap, then awkwardly raised it and rested it on the arm of the chair. He was conscious of his face burning red.

“As I was saying,” the man sitting opposite continued, “when you procreate, your progeny inherits DNA from you and from your partner. This combined coding will then intermingle with yet another set of DNA when your progeny has a son or a daughter. Are you with me?”

“I get the gist of it,” Fogg lied.

“In recent years, it has been discovered that DNA contains a great deal more than initially thought. It doesn’t merely pass selected aspects of your forebears’ physical appearance on to you; it also contains their personalities, their histories, and their predilections. Elements of these help to form your disposition, and guide you in the day to day business of living, but they do not entirely prescribe your actions. You have free will, and in using it, you grow and develop into a unique individual, and you—how shall I put this?—you etch new characteristics into the code of your own DNA.”

“Enthralling,” Fogg said. “Do you happen to have a cigar?”

“A what?”

“Cigar. Tobacco.”

“Are you joking? Of course not!”

Fogg risked another glance down at himself. Herself.

“DNA,” he muttered. “Marvellous. Spiffing. Why am I a woman?”

“My sister and I specialise in DNA research. We discovered that, in any given individual, DNA contains the complete and detectable recordings of at least twelve generations that went before. It is only beyond that twelfth generation—working backward in history—that the code gradually becomes obscured, or, at least, too complex to be isolated.”

“By golly!” Fogg exploded. “I have not the slightest notion what you are babbling about! Will you please start talking English and tell me why the dickens I am here, in—in—” He gestured down at himself. “In this!”

The professor looked perplexed. “I’m sorry! I know it’s complicated. Let me cut to the chase. Basically, what has happened is this. My sister and I managed to distinguish, and cordon off, if you will, a complete section of code in her DNA—the entire record of one of our ancestors, his memory, his personality, his intellect, the lot. We then created a chemical formula—a molecular chain—which, when suspended in a liquid and digested, targets that specific component of the DNA and causes it to amplify. For as long as the drug is effective, the ancestor’s entire personality becomes dominant, completely obliterating that of its host—in this case, Miriam. We first performed the experiment, successfully, last month, when we resurrected your great great great grandfather, Doctor Bartholomew Charles Fogg. Unfortunately, his outlook on life was so coloured by the religious views of his time that he didn’t properly comprehend my explanation of the process. He somehow managed to talk circles around me, and interpreted my replies in terms of good and evil, until he’d convinced himself that the cells of the body contain in them the pure essences of those two qualities. Personally, I found his thought processes baffling, which is why Miriam and I hoped that, when we isolated a second section of code and repeated the experiment, we’d resurrect a more recent relative. You, sir, are the result. So, to finally answer your question, Mr Fogg: you aren’t really here at all. You are long dead.”

“Oh, well, thank you, that’s just wonderful. I feel much relieved,” Fogg responded, sarcastically. “And, incidentally, all that gobbledegook is utter claptrap, for it just so happens t

hat I don’t have any children, so you can't possibly be my however-many-greats-it-was grandson.”

Professor Xavier Fogg rubbed his chin and consulted the document again. “As I said, it’s interesting that you regard yourself as—what? Thirty-seven years old? Your self-awareness seems to have focused on the period of life when you were at, I daresay, your peak. You don't remember anything from later than 1857?”

“No, I don't.”

“Hmm. We’ll have to look into that. As for your son, Derwent James Fogg; well, let us say you were blessed rather later in life than the average man of your time.”

Fogg grunted. “It’s nice to know I’ll still be capable. What is Hetrodythermaline?”

The professor clicked his tongue. “Ah. Hetrodythermaline is what we call the formula. It must be wearing off already. Miriam took only a small dose. Her personality is obviously reasserting itself. You’ll now find things you don’t understand—from her mind—popping into your head, then they’ll overwhelm you and you’ll be gone and Miriam will be back.”

“And something called the—um—the Ramones?”

“Her favourite group from the old days.”

“Group of what?”

“Classical musicians. It’s been good to meet you, Grandpa.”

“Don’t bloomin’ well call me that! And if you must fiddle with nature, in future leave me out of it!”

“I will. Sorry.”

“I say, shall I remember any of this?”

“Remember it when? As I said, you’re long dead.”

Fogg’s vision began to narrow, as if he was slipping into a long tunnel. Fragmented, nonsensical thoughts crowded into his head. He wondered what StringComps and BioProcs were. CellComps and iPatches and GenMem and Deep User Entwining and ClusterComps and KFC Retro.

The professor’s voice came from far away. “But, on the other hand, we have a theory that time itself is a function of DNA, and since time has been proven to move in all directions, it wouldn’t surprise me at all if you find yourself back in 1857 with some memory of this. Perhaps, if that happens, you could—”

He was gone.

Miriam’s voice said, “Sleeping again! You really are the most confoundedly lazy man I have ever known!”

The fire snapped and rustled in the hearth.

He heard a hawker outside yelling, “Gingerbread! Hot Spiced gingerbread! Nice smoking hot! Come buy my gingerbread, hot spiced gingerbread!”

“Wake up! It’s not even two o’clock!”

That’s not my voice, he thought. I mean, it’s not Doctor Miriam Fogg’s voice. That’s Mrs Boswell.

He opened his eyes and, glancing around, saw that he was at home, in his lounge or workshop or study or whatever the untidy, disorganised room was called, and, right in front of him, his secretary was standing with flashing indignant eyes and fists upon hips. There was a copy of The London Bugle in her right hand.

“Remind me, Mrs Boswell,” he said. “Who is Miriam Fogg?”

“I’ve never heard of her. Your sister?”

“No, her name is Stephanie.”

“Mother?”

“Georgina.”

“Aunt? Cousin? Niece? How on earth should I know? Now, how about heaving yourself out of that blessed armchair and doing something about this?” She unfurled the newspaper and held it out so he could see the headline.

“Ah!” he said. “Mars is still alive with lights, I see! What the devil is going on up there, do you think?”

“Not that headline!” Emma snapped. “This one!”

She pointed at an announcement that read: JASON GRENFELL MISSING!

“Humph! The lad vanished three months ago,” Fogg said.

Emma looked surprised. “How do you know that? Lord Grenfell has only just made it public. He thought his son was just off on a jaunt until he realised how much time had passed without word from him.”

“I heard it from Gordon Quayle.”

“Who?”

“Another of Baker Street’s resident detectives. He lives a few doors down. Number 98. Grenfell hired him to find junior.”

“Which, obviously, he didn’t.”

“Correct, though he discovered that one of Jason’s friends, Gerald von Horst, went missing at the same time and hasn’t been seen since. I daresay Grenfell’s initial thought was the right one; the two of ‘em are simply off exploring the world.”

Emma sighed and dropped the newspaper onto her armchair.

“Very well, no work there then. But, really sir, you need to find yourself a client. It’s been two weeks since your last case!”

“Humph! The Mystery of the Misplaced Comma.”

“Yes. An affair so humdrum and uninspiring that I had little choice but to resort to formulaic nonsense in my writing up of it for The Baker Street Detective.”

Fogg suddenly jumped to his feet and cried out, “Formula! By golly, Mrs. Boswell! Get me a pen and paper! At once!”

“A simple ‘please’ wouldn’t go amiss.”

“Now!” he bellowed. “No time for niceties! This is an emergency!”

He strode over to one of his workbenches and, with a sweep of his arm, cleared a space. Tools, small items of machinery, blueprints, screws, and nuts and bolts went cascading noisily to the floor.

Emma Boswell opened her mouth to object but, noticing Fogg’s expression, decided to keep quiet. She took a notepad and pen from her desk and delivered them to him. Without so much as a thank you, he snatched them out of her hand and started scribbling with a manic energy.

She looked over his shoulder. “What is it?”

“A chemical formula. Hetrodythermaline.”

Emma stifled a groan. Macallister Fogg’s chemical experiments had often resulted in some of the worst odours she’d ever experienced; more fetid even, than the fumes that rose from the River Thames.

“Did you dream it?” she asked. “The formula?”

He didn’t reply, and, after watching for a few moments more, Emma shook her head despairingly and left him to it.

II

By half past four, Fogg was setting up flasks, beakers and bottles, Bunsen burners, pipettes, test tubes, funnels, condensers and filter adapters. He gave Emma a shopping list and sent her to Mulburry & Co. Chemical Supplies on Praed Street.

“I’m barely aware of what I’m doing, Mrs B!” he announced upon her return. “I have a vague conception of how this formula acts upon the body, but I have no idea how I know what I know!”

“On the body?” she replied in a shocked tone. “Are you creating some sort of tonic?”

He accepted a large brown paper bag from her and began to unpack from it sachets and vials and bottles.

“No, my dear. I’m creating the means to investigate an ages-old crime! One that occurred in my very own family!”

“What crime? How?”

“In 1745, my great great grandfather, Doctor Cyrus Brentwood Fogg, murdered his brother, a vicar, the Reverend Leonard Thomas Fogg, before embarking on a crime spree of unprecedented scale. Four years later, the authorities had him on the run, and he was forced to hide in Epping Forest, where he continued his iniquitous activities, only now as a highwayman. He was finally captured and hanged in 1750.”

“Good gracious!” Emma Boswell exclaimed.

“The mystery is, what drove him to it? My great grandfather—Cyrus Fogg’s son—might have known the answer, but not only did he refuse to speak of it, but he also saw to it that all records pertaining to his father were destroyed.”

“But surely there are surviving newspaper reports?”

Fogg poured a glutinous red liquid into a round-bottom flask then added a white powder. The smell of rotting eggs filled the room. Emma pulled out a handkerchief and held it to her nose.

“There are, and I’ve seen them. In fact, it was while exploring my family’s dark past that I decided to become a consulting detective. You see, Mrs Boswell, ever since I was a young lad, I’ve always wondered what sent Cyrus awry—what s

ends anyone awry. And perhaps, too, there is something of him within me that seeks to atone for his sins.”

As clear as a bell, he suddenly heard the words, his memory, his personality, his intellect, the lot.

“What?” he asked.

“I didn’t speak, Mr Fogg,” Emma answered.

The detective peered around the room. There was no one else present.

“Humph! Well, anyway, the newspaper reports are singularly unhelpful. They reveal that my ancestor was a master of disguise, that he extorted money from a shipping magnate, robbed four banks at gunpoint, swindled a number of financiers out of a fortune, sold state secrets to a foreign power, murdered at least six men, and established a crime syndicate that operated throughout the country. Such was his organisational skill, and strategic cunning in all matters nefarious, that journalists dubbed him ‘the Archduke of Depravity.’ None, though, revealed the motive for his original villainy; the murder, by poisoning, of his brother.”

“My goodness! To think that you’re descended from such a scoundrel!” Emma murmured from behind her handkerchief. “It explains a lot. May I open a window?”

“Please don’t. A blast of cold air might adversely affect the chemical processes.”

“I’m at a loss, sir. How will this concoction you’re creating help to solve the mystery of Doctor Cyrus Fogg?”

Her employer scratched his head. “The funny thing is, Mrs Boswell, I’m not entirely sure. Somehow, though, I feel certain that the tincture, once swallowed, will enable Cyrus Fogg, or his son, or perhaps his father, to manifest through me, at which point you can interview him.”

Emma slowly closed then opened her eyes. She gave a long sigh, and muttered, “I felt certain it would happen one day, I just didn’t expect it so soon.”

“Expect what?”

“You to completely lose your mind. I’m afraid it’ll be Bedlam for you, sir. Never fear, I shall visit from time to time. I’ll bring titbits to cheer you up. Are you still fond of butterscotch? What about sugar-glazed teacakes?”

The Secret of Abdu El Yezdi

The Secret of Abdu El Yezdi The Return of the Discontinued Man

The Return of the Discontinued Man The Rise of the Automated Aristocrats

The Rise of the Automated Aristocrats Macallister Fogg 2: Great Great Great (And So Forth) Uncle Dragoslav

Macallister Fogg 2: Great Great Great (And So Forth) Uncle Dragoslav Sexton Blake and the Great War

Sexton Blake and the Great War A Red Sun Also Rises

A Red Sun Also Rises Macallister Fogg 3: The Hetrodythermaline Highwayman

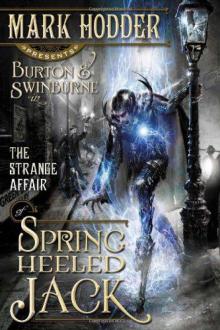

Macallister Fogg 3: The Hetrodythermaline Highwayman The Strange Affair of Spring Heeled Jack

The Strange Affair of Spring Heeled Jack Macallister Fogg 1: The Master Mummer's Mummy (The Adventures of Macallister Fogg)

Macallister Fogg 1: The Master Mummer's Mummy (The Adventures of Macallister Fogg) Expedition to the Mountains of the Moon bas-3

Expedition to the Mountains of the Moon bas-3 The Return of the Discontinued Man (A Burton & Swinburne Adventure)

The Return of the Discontinued Man (A Burton & Swinburne Adventure) Red Sun Also Rises, A

Red Sun Also Rises, A The curious case of the Clockwork Man bas-2

The curious case of the Clockwork Man bas-2 The strange affair of Spring-heeled Jack bas-1

The strange affair of Spring-heeled Jack bas-1