- Home

- Mark Hodder

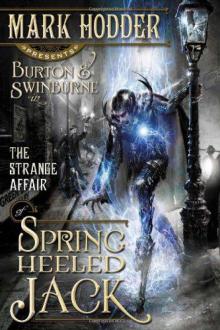

The strange affair of Spring-heeled Jack bas-1 Page 2

The strange affair of Spring-heeled Jack bas-1 Read online

Page 2

"Don't step back!" he roared. "They'll think that we're retiring!"

Speke looked at him with an expression of utter dismay and, right there, in the midst of battle, their friendship ended, for John Hanning Speke knew that his cowardice had been recognised.

A club struck Burton on the shoulder and, tearing his eyes away from the other Englishman, he spun and swiped his blade at its owner. He was jostled back and forth. One set of hands kept pushing at his back, and he wheeled impatiently, raising his sword, only recognising El Balyuz at the very last moment.

His arm froze in midswing.

His head exploded with pain.

A weight pulled him sideways and he collapsed onto the stony earth.

Dazed, he reached up. A barbed javelin had transfixed his face, entering the left cheek and exiting the right, knocking out some back teeth, cutting his tongue, and cracking his palate.

He fought to stay conscious.

Someone started dragging him away from the conflict.

He passed out.

In front of the Rowtie, Speke, driven to a fury by the exposure of the shameful flaw in his character, strode into the melee, raised his Dean and Adams revolver, pressed its muzzle against the chest of the man who'd downed Burton, and pulled the trigger.

The gun jammed.

"Blast it!" said Speke.

The tribesman, a massive warrior, looked down at him, smiled, and punched him over the heart.

Speke fell to his knees, gasping for air.

The Somali bent, took him by the hair, pulled him backward, and, with his other hand, groped between Speke's legs. For an instant, the Englishman had the terrifying conviction that he was going to be unmanned. The tribesman, though, was simply checking for daggers, hidden in the Arabic fashion.

Speke was thrust onto his back and his hands were quickly tied together, the cords pulled cruelly tight. Yanked upright, he was marched away from the camp, which was now being looted and destroyed.

Lieutenant Burton regained his wits and found that he was being pulled toward the beach by El Balyuz. He recovered himself sufficiently to stop his rescuer and to order the man, via sign language and writing in a patch of sand, to go and fetch the small boat that the expedition party had moored in the harbour, and to bring it to the mouth of a nearby creek.

El Balyuz nodded and ran off.

Burton lay on his back and gazed at the Milky Way.

I want to live! he thought.

A minute or so passed. He raised a hand to his face and felt the barbed point of the javelin. The only way to remove it was by sliding the complete length of the shaft through his mouth and cheeks. He took a firm grip on it, pushed, and fainted.

As the night wore on, John Speke was taunted and spat upon by his captors. With their sabres, they sliced the air inches from his face. He stood and endured it, his eyes hooded, his jaw set, expecting to die, and he wondered what Richard Burton would say about him when reporting this incident.

Don't step back! They'll think that we're retiring!

The rebuke had stung, and if Burton put it on record, Speke would be forever branded as less than a man. Damn the arrogant blackguard!

One of his captors casually thrust his spear through Speke's side. The lieutenant cried out in pain, then fell backward as the point pierced him again, this time in the shoulder.

This is the end, he told himself.

He struggled back to his feet and, as the spear was stabbed at his heart, deflected it with his bound hands. The point tore the flesh behind his knuckles to the bone.

The Somali stepped back.

Speke straightened and looked at him.

"To hell with you," he said. "I won't die yellow."

The tribesman leaped in and prodded the spear into Speke's left thigh. The explorer felt the blade scrape against bone.

"Shit!" he coughed in shock, and grabbed reflexively at the shaft. He and the African fought over it-one trying to gain possession, the other struggling to retain it. The Somali let go with his left hand and used it to pull a shillelagh from his belt. He swiped at Speke's right arm and the cudgel connected with a horrible crack. Speke dropped the spear shaft and crumpled to his knees, gasping with agony.

His attacker walked away, turned back, and ran at him, plunging the spear completely through the Englishman's right thigh and into the ground beyond.

Speke screamed.

Instinct took over.

With his awareness strangely separated from his body, he watched as his hands gripped the weapon, pulled it free of the ground, out through his thigh, and threw it aside. Then he stumbled into his attacker and his bound fists swept up, smashing into the man's face.

The warrior rocked back, raising a hand to his face as blood spurted from his nose.

Speke half walked, half hopped away, his disengaged mind wondering how he was staying upright with such terrible injuries.

Where's the pain? he mused, entirely unaware that he was afire with it.

He hobbled, barefoot, across jagged rock, down a slope, and onto the shingle of the beach. Somehow, he started to run. What tatters of clothing remained on him streamed behind.

The Somali snatched up the spear and gave chase, threw the weapon, missed, and gave up.

Other tribesmen lunged for the Englishman but Speke dodged them and kept going. He outdistanced his pursuers and, when he saw that they'd given up the chase, he collapsed onto a rock and chewed through the cord that bound his wrists.

He was faint with shock and loss of blood but knew that he had to find his companions, so, as dawn broke, he pushed on until he reached Berbera. Here he was discovered by a search party led by Lieutenant Herne and was carried to the boat at the mouth of the creek. He'd run for three miles and had eleven wounds, including the two that had pierced the large muscles of his thighs.

They placed him onto a seat and he raised his head and looked at the man sitting opposite. It was Burton, his face bandaged, blood staining the linen over his cheeks.

Their eyes met.

"I'm no damned coward," whispered Speke.

The battle should have made them brothers. They both acted as if it hadand less than two years later they embarked together on one of the greatest expeditions in British history: a perilous trek into central Africa to search for the source of the Nile.

Side by side, they endured extreme conditions, penetrating into lands unseen by white men and skirting dangerously close to Death's realm. An infection temporarily blinded and immobilised Burton. Speke became permanently deaf in one ear after attempting to remove an insect from it with a penknife. They were both stricken with malaria, dysentery, and crippling ulcers.

They pressed on.

Speke's resentment simmered.

He constructed his own history of the Berbera incident, excising from it the most essential element: the fact that a thrown stone had cracked against his kneecap, causing him to step back into the Rowtie's entrance. Burton had looked around at that very instant and had plainly seen the stone bounce off Speke's knee and understood the back-step for the reaction it was. He'd never for one moment doubted his companion's courage.

Speke knew the stone had been seen but chose to forget it. History, he discovered, is what you make it.

They reached the central lakes.

Burton explored a large body of water called by the local tribes "Tanganyika," which lay to the south of the Mountains of the Moon. His geographical readings suggested that it could be the Nile's source, though he was too ill to visit its northernmost shore from whence the great river should flow.

Speke, leaving his "brother" in a fevered delirium, trekked northeastward and found himself at the shore of a vast lake, which he imperiously named after the British monarch, though the tribes that lived on its shores already had a name for it: "Nyanza."

He tried to circle it, lost sight of it, found it again farther to the northor was it the shore of a second lake?-took incomplete, incompetent measurements, and returned to Burto

n, the leader of the expedition, claiming to have found, on his own and without a shadow of a doubt, the true source of the great river.

They recovered a modicum of health and undertook the long march back to Zanzibar where Burton fell into a fit of despondency, blaming himself for what, by his demanding standards, was inconclusive evidence.

John Speke, less scientific, less scrupulous, less disciplined, sailed back to England ahead of Burton and en route fell under the influence of a man named Laurence Oliphant, an arch-meddler and poseur who kept a white panther as a pet. Oliphant nurtured Speke's pique, turned it into malice, and seduced him into claiming victory. No matter that it was the other man's expedition; Speke had solved the biggest geographical riddle of the age!

John Speke's last words to Burton had been "Good-bye, old fellow; you may be quite sure I shall not go up to the Royal Geographical Society until you have come to the fore and we appear together. Make your mind quite easy about that."

The day he landed in England, Speke went straight up to the Royal Geo graphical Society and told Sir Roderick Murchison that the Nile question was settled.

The Society divided. Some of its members supported Burton, others supported Speke. Mischief makers stepped in to ensure that what should have been a scientific debate rapidly degenerated into a personal feud, though Burton, now recovering his health in Aden, was barely aware of this.

Easily swayed, Speke became overconfident. He began to criticise Burton's character, a dangerous move for a man who believed that his cowardice had been witnessed by his opponent.

Word reached Burton that he was to be awarded a knighthood and should return to England at once. He did so, and stepped ashore to find himself at the centre of a maelstrom.

Even as the reclusive monarch's representative touched the sword to his shoulders and dubbed him Sir Richard Francis Burton, the famous explorer's thoughts were on John Speke, wondering why he was taking the offensive in such a manner.

Over the following weeks, Burton defended himself but resisted the temptation to retaliate.

Life is fickle; the fair man doesn't invariably win.

Lieutenant Speke, it gradually became apparent, had made a lucky guess: the Nyanza probably was the source of the Nile.

Murchison knew, as Burton had been quick to point out, that Speke's readings and calculations were badly faulted. In fact, they were downright amateurish and not at all admissible as scientific evidence. Nevertheless, there was in them the suggestion of a potential truth. This was enough; the Society funded a second expedition.

John Speke went back to Africa, this time with a young, loyal, and opinion-free soldier named James Grant. He explored the Nyanza, failed to circumnavigate it, didn't find the Nile's exit point, didn't take accurate measurements, and returned to England with another catalogue of assumptions which Burton, with icy efficiency, proceeded to pick to pieces.

A face-to-face confrontation between the two men seemed inevitable.

It was gleefully engineered by Oliphant, who had, by this time, mysteriously vanished from the public eye-into an opium den, according to rumour-to pull strings like an invisible puppeteer.

He arranged for the Bath Assembly Rooms to be the venue and September 16, 1861, the date. To encourage Burton's participation, he made it publicly known that Speke had said: "If Burton dares to appear on the platform at Bath, I will kick him!"

Burton had fallen for it: "That settles it! By God, he shall kick me!"

The hansom drew up outside the Royal Hotel, and Burton's mind reengaged with the present. He emerged from the cab with one idea uppermost: someday, Laurence Oliphant would pay.

He entered the hotel. The receptionist signalled to him; a message from Isabel was waiting.

He took the note and read it:

John was taken to London. On my way to Fullers' to find out exactly where.

Burton gritted his teeth. Stupid woman! Did she think she'd be welcomed by Speke's family? Did she honestly believe they'd tell her anything about his condition or whereabouts? As much as he loved her, Isabel's impatience and lack of subtlety never failed to rile him. She was the proverbial bull in a china shop, always charging at her target without considering anything that might lie in her path, always utterly confident that what she wanted to do was right, whatever anyone else might think.

He wrote a terse reply:

Left for London. Pay, pack, and follow.

He looked up at the hotel receptionist. "Please give this to Miss Arundell when she returns. Do you have a Bradshaw?"

"Traditional or atmospheric railway, sir?"

"Atmospheric."

"Yes, sir."

He was handed the train timetable. The next atmospheric train was leaving in fifty minutes. Time enough to throw a few odds and ends into a suitcase and get to the station.

THE THING IN THE ALLEY

The Eugenicists are beginning to call their filthy experimentations "genetics," after the Ancient Greek "genesis," meaning "Origin." This is in response to the work of Gregor Mendel, an Augustinian priest. A priest! Can there be any greater hypocrite than a priest who meddles with Creation?

- RICHARD MORMON MILKES

It was a fast and smooth ride to London.

Isambard Kingdom Brunel's atmospheric railway system was a triumph. It used wide-gauge tracks in the centre of which ran a fifteen-inch-diameter pipe. Along the top of the pipe there was a two-inch slot, covered with a flapvalve of oxhide leather. Beneath the front carriage of each train hung a dumbbell-shaped piston, which fitted snugly into the pipe. This was connected to the carriage by a thin shaft that rose through the slot. The shaft had a small wheeled contrivance attached to it that pressed open the leather flap at the front while closing and oiling it at the back. Every three miles along the track, a station sucked air out of the pipe in front of the train and pumped it back in behind. It was this difference in air pressure that shot the carriages along the tracks at tremendous speed.

When Brunel first created the system he encountered an unexpected problem: rats ate the oxhide. He turned to his Eugenicist colleague, Francis Galton, for a solution, and the scientist had provided it in the form of specially bred oxen whose skin was both repellent and poisonous to the rodents.

The pneumatic rail system now ran the length and breadth of Great Britain and was being extended throughout the Empire, particularly in India and South Africa.

A similar method of propulsion was planned for the new London Under ground railway system, though this project had been delayed since Brunel's death two years ago.

Burton arrived home at 14 Montagu Place at half past six, by which time a mist was drifting through the city streets. As he opened the wrought-iron gate and stepped to the front door, he heard a newsboy in the distance calling: "Speke shoots himself. Nile debate in uproar! Read all about it!"

He sighed and waited for the young urchin to draw closer. He recognised the soft Irish accent; it was Oscar, a refugee from the never-ending famine, whose regular round this was. The boy possessed an extraordinary facility with words, which Burton thoroughly appreciated.

The youngster approached, saw him, and grinned. He was a short and rather plump lad, about eight years old, with sleepy-looking eyes and a cheeky grin marred only by crooked, yellowing teeth. He wore his hair too long and was never without a battered top hat and a flower in his buttonhole.

"Hallo, Captain! I see you're after making the headlines again!"

"It's no laughing matter, Quips," replied Burton, using the nickname he'd given the newspaper boy some weeks previously. "Come into the hallway for a moment; I want to talk with you. I suppose the journalists are all blaming me?"

Oscar joined the explorer at the door and waited while he fished for his keys.

"Well now, Captain, there's much to be said in favour of modern journalism. By giving us the opinions of the uneducated, it keeps us in touch with the ignorance of the community."

"Ignorance is the word," agreed Burton. He opened the do

or and ushered the youngster in. "If the reaction of the crowd in Bath is anything to go by, I rather suspect that the charitable are saying Speke shot himself, the uncharitable that I shot him."

Oscar laid his bundle of newspapers on the doormat.

"You're not wrong, sir; but what do you say?"

"That no one currently knows what happened except those who were there. That maybe it wouldn't have happened at all had I tried a little harder to bridge the divide that opened between us; been, perhaps, a little more sensitive to Speke's personal demons."

"Ah, demons, is it?" exclaimed the boy, in his high, reedy voice. "And what of your own? Are they not encouraging you to luxuriate in selfreproach?"

"Luxuriate!"

"To be sure. When we blame ourselves, we feel no one else has a right to blame us. What a luxury that is!"

Burton grunted. He put his cane in an elephant-foot umbrella stand, placed his topper on the hatstand, and slipped out of his overcoat.

"You are a horribly intelligent little ragamuffin, Quips."

Oscar giggled. "It's true. I'm so clever that sometimes I don't understand a single word of what I'm saying!"

Burton lifted a small bell from the hall table and rang for his housekeeper.

"But is it not the truth, Captain Burton," continued the boy, "that you only ever asked Speke to produce scientific evidence to back up his claims?"

"Absolutely. I attacked his methods but never him, though he didn't extend to me the same courtesy."

They were interrupted by the appearance of Mrs. Iris Angell, who, though Burton's landlady, was also his housekeeper. She was a wide-hipped, white-haired old dame with a kindly face, square chin, and gloriously blue and generous eyes.

"I hope you wiped your feet, Master Oscar!"

"Clean shoes are the measure of a gentleman, Mrs. Angell," responded the boy.

"Well said. There's a freshly baked bacon and egg pie in my kitchen. Would you care for a slice?"

"Very much so!"

The Secret of Abdu El Yezdi

The Secret of Abdu El Yezdi The Return of the Discontinued Man

The Return of the Discontinued Man The Rise of the Automated Aristocrats

The Rise of the Automated Aristocrats Macallister Fogg 2: Great Great Great (And So Forth) Uncle Dragoslav

Macallister Fogg 2: Great Great Great (And So Forth) Uncle Dragoslav Sexton Blake and the Great War

Sexton Blake and the Great War A Red Sun Also Rises

A Red Sun Also Rises Macallister Fogg 3: The Hetrodythermaline Highwayman

Macallister Fogg 3: The Hetrodythermaline Highwayman The Strange Affair of Spring Heeled Jack

The Strange Affair of Spring Heeled Jack Macallister Fogg 1: The Master Mummer's Mummy (The Adventures of Macallister Fogg)

Macallister Fogg 1: The Master Mummer's Mummy (The Adventures of Macallister Fogg) Expedition to the Mountains of the Moon bas-3

Expedition to the Mountains of the Moon bas-3 The Return of the Discontinued Man (A Burton & Swinburne Adventure)

The Return of the Discontinued Man (A Burton & Swinburne Adventure) Red Sun Also Rises, A

Red Sun Also Rises, A The curious case of the Clockwork Man bas-2

The curious case of the Clockwork Man bas-2 The strange affair of Spring-heeled Jack bas-1

The strange affair of Spring-heeled Jack bas-1