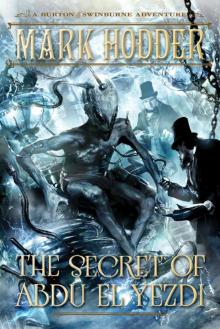

The Secret of Abdu El Yezdi

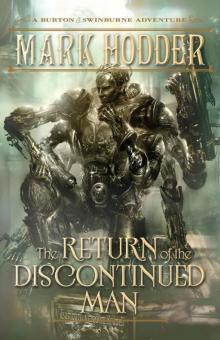

The Secret of Abdu El Yezdi The Return of the Discontinued Man

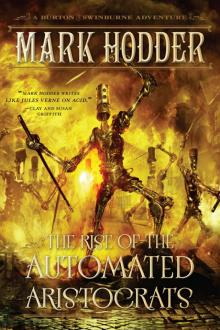

The Return of the Discontinued Man The Rise of the Automated Aristocrats

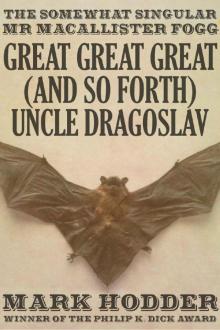

The Rise of the Automated Aristocrats Macallister Fogg 2: Great Great Great (And So Forth) Uncle Dragoslav

Macallister Fogg 2: Great Great Great (And So Forth) Uncle Dragoslav Sexton Blake and the Great War

Sexton Blake and the Great War A Red Sun Also Rises

A Red Sun Also Rises Macallister Fogg 3: The Hetrodythermaline Highwayman

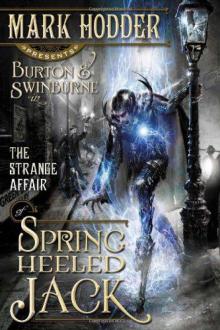

Macallister Fogg 3: The Hetrodythermaline Highwayman The Strange Affair of Spring Heeled Jack

The Strange Affair of Spring Heeled Jack Macallister Fogg 1: The Master Mummer's Mummy (The Adventures of Macallister Fogg)

Macallister Fogg 1: The Master Mummer's Mummy (The Adventures of Macallister Fogg) Expedition to the Mountains of the Moon bas-3

Expedition to the Mountains of the Moon bas-3 The Return of the Discontinued Man (A Burton & Swinburne Adventure)

The Return of the Discontinued Man (A Burton & Swinburne Adventure) Red Sun Also Rises, A

Red Sun Also Rises, A The curious case of the Clockwork Man bas-2

The curious case of the Clockwork Man bas-2 The strange affair of Spring-heeled Jack bas-1

The strange affair of Spring-heeled Jack bas-1